21st Century Council Meets to Discuss Salvaging Globalization

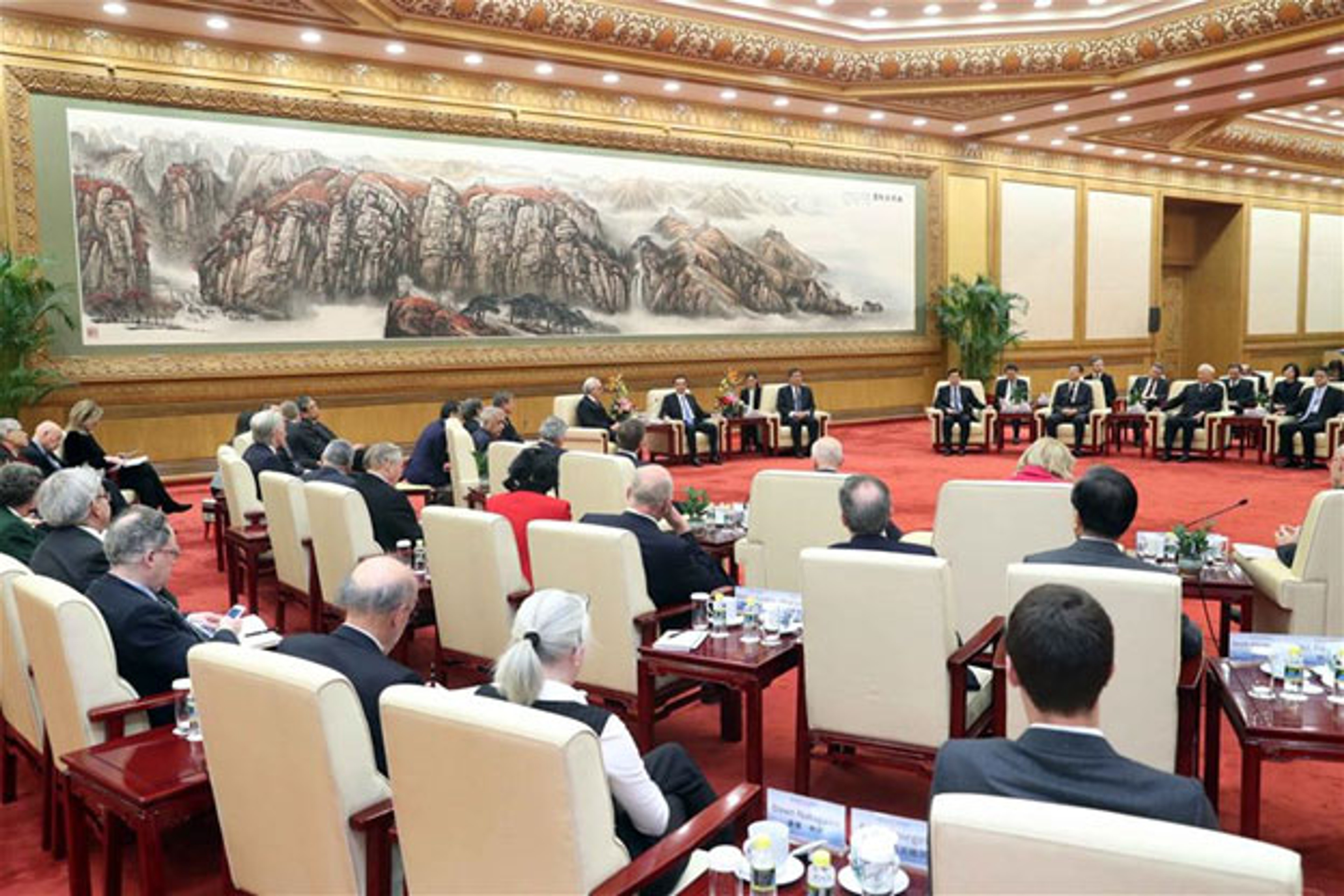

On December 15-16 the Berggruen Institute’s 21st Century Council met in New York City to discuss how to rethink globalization in light of the shocks to politics and institutions that have occurred all over the West.

Participants included Gordon Brown, Frank Fukuyama, Mario Monti, Fareed Zakaria, Arianna Huffington, Nouriel Roubini, Kishore Mahbubani, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, and Shaukat Aziz, among others.

The following working paper was prepared in advance to stimulate conversation among the many world leaders and thinkers who attended about how to best adapt globalization for the future.

Salvaging Globalization

At the Global Progress 2016 conference in Montreal in September, Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s Vice-Chancellor and head of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), concisely captured the backlash roiling politics in his country and the rest of Europe. As average citizens see it, he said, “first the authorities spent billions on bailing out the banks, and now are spending generously on refugees — meanwhile cutting back on pensions, unemployment payments and other benefits through austerity policies. ‘What about us?’ they ask.

Sadiq Khan, the new Muslim mayor of London found a similar resentment among pro-Brexit voters that others were being put first by elites disconnected from their concerns. The Brexiters blamed the European Union authorities and immigrants for what ailed them even if they had nothing to do with British problems. “People who couldn’t get their child into a pre-school program blamed the EU. If they couldn’t find affordable elderly care for their parents, they blamed the EU. In short, the Brexit backlash identified all the ills of society with European integration.”

In the U.S., even as the unemployment rate fell to 4.9 per cent (with stark regional differences), median household income rose and there was net migration back to Mexico, Donald Trump swept into power with his mantra that the cosmopolitan governing elites have failed to protect jobs and promote the interests of ordinary Americans first – certainly true for his core constituency of the non-college educated white working class left behind by globalization and policy inattention. Steve Bannon, Trump’s top campaign strategist who has since moved into the White House, could not be more clear about the reason for victory and the intent going forward. ” I’m an economic nationalist,” Bannon says. “The globalists gutted the American working class and created a middle class in Asia. The issue now is about Americans looking to not get f—ed over. If we deliver we’ll get 60 percent of the white vote, and 40 percent of the black and Hispanic vote and we’ll govern for 50 years. That’s what the Democrats missed. They were talking to these people with companies with a $9 billion market cap employing nine people. It’s not reality. They lost sight of what the world is about.”

The sociologist Arlie Hochschild, in her book “Strangers in Their Own Land,” explains the emotions behind Tea Party sympathizers through case studies in Louisiana. According to Hochschild, they feel as if they’ve been standing still, waiting in a long line for the American Dream, and then others championed by the elite custodians of the status quo (immigrants, the poor on subsidies, LGBT rights, the 1% with their carried interest tax breaks, Wall St. bankers) get to “cut in” ahead of them.

Challenges unrelated to trade agreements such as the rapid displacement of full time work by intelligent machines or the advent of precarious gig labor in the sharing economy, are also cast into the basket of anxieties associated with globalization.

Photo Credit: Slava Bowman

You can pick your study on the varying impacts of trade and technology, and there is evidence for both as a cause of growing inequality and job losses in some sectors.

George Mason University’s Daniel Griswold sees a shift in the composition of American manufacturing rather than its demise. “In the last 20 years,” he has written, “real, inflation-adjusted U.S. manufacturing output has increased by almost 40 per cent. Annual value added by U.S. factories has reached a record $2.4 trillion. What has changed in recent decades is what our factories produce. Americans today make fewer shirts, shoes, toys and tables than we did 30 years ago. Instead, America’s 21st century manufacturing sector is dominated by petroleum refining, pharmaceuticals, plastics, fabricated metals, machinery, computers and other electronics, motor vehicles and other transportation equipment, and aircraft and aerospace equipment.”

Not insignificantly, the rise in output Griswold points to has been due in good part to the automation of advanced manufacturing sectors. A recent study by the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University places the blame for most of the labor displacement of recent decades on productivity growth, which the report says caused 85 per cent of the job losses in manufacturing from 2000 to 2010, a period that saw 5.6 million factory jobs disappear. In that same period, trade accounted for a mere 13% of job losses, the study reports.

Robert Scott of the Economic Policy Institute takes a more indiscriminate brush to the issue and puts the onus on the U.S. trade deficit. According to his study, the U.S. lost 5 million manufacturing jobs between January 2000 and December 2014. “There is a widespread misperception,” he argues, “that rapid productivity growth is the primary cause of continuing manufacturing job losses over the past 15 years. Instead job losses can be traced to growing trade deficits in manufacturing products prior to the Great Recession and then the massive output collapse during the Great Recession.”

To a significant degree, the job loss damage of globalization in key areas of manufacturing in advanced economies has already happened; its pain is only now being registered politically. Going forward, the inequality gap this has opened up, even as global equality has improved, will be compounded by technological upheaval of labor markets. As MIT’s Eric Brynjolfsson observes, “off-shoring is only the way-station to the automation of labor.” Toomas Ives, the former e-savvy president of Estonia, sees an even greater populist tsunami coming in reaction as the creative-destructive churn of innovation accelerates and displaces labor at a far greater level than trade.

What is clear is that real and imagined issues rooted in entirely different causes are conflated in the mounting backlash against global integration and merged into a generalized anxiety, amplified by social media’s mix of truths and untruths, that translates into distrust of public institutions and governing elites. Those with a populist bent place their hope and expectations in extreme politics that offer simple quick fixes instead of enduring solutions, and, in some cases, put their trust in authoritarian tribunes and popular plebiscites seen as more effective in serving their interests than the complexity, messiness and seemingly endless gridlock of representative democracy.